Why Central Oregon is Called "High Desert Country": Unpacking a Unique Landscape

Why Central Oregon is Called "High Desert Country": Unpacking a Unique Landscape

I. Introduction: A Land of Striking Contrasts

Central Oregon conjures images of snow-capped peaks, lush pine forests, and winding rivers. Yet, it is widely known as "High Desert Country," a designation that often sparks curiosity and even confusion. How can a region with such varied landscapes be called a desert? This apparent contradiction is precisely what makes Central Oregon so intriguing.

This seemingly contradictory name hints at a deeper story – one of dramatic geological forces, unique climatic patterns, and a rich history that shaped both the land and its nomenclature. It is not the sandy, cactus-filled desert many might imagine, but rather a vibrant, high-altitude environment with its own distinct character. This exploration will delve into the geographical, geological, climatic, and historical reasons behind Central Oregon's "High Desert Country" moniker, revealing the fascinating science and story behind this remarkable region.

II. Defining the "High Desert": More Than Just Arid Land

To understand Central Oregon's "High Desert" designation, it is helpful to first grasp what generally defines a desert. Deserts are typically characterized by extremely low, sporadic rainfall, often receiving no more than ten inches annually. This precipitation frequently comes in short, violent downpours, leading to rapid runoff and flash floods, with much moisture lost to evaporation. American deserts can experience evaporation rates ranging from 70 to 160 inches per year. Deserts also experience seasonal high temperatures, minimal cloud cover allowing significant solar radiation to reach the surface, wide daily temperature ranges (often 50 degrees Fahrenheit or more), and strong, dry winds that further increase evaporation.

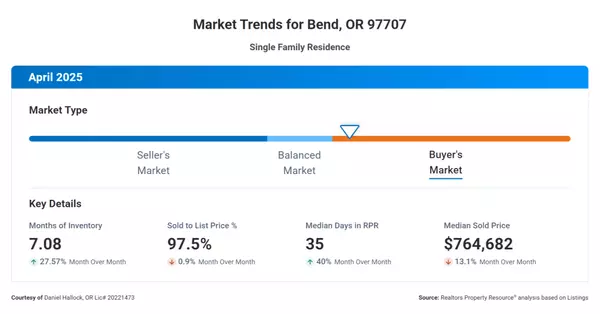

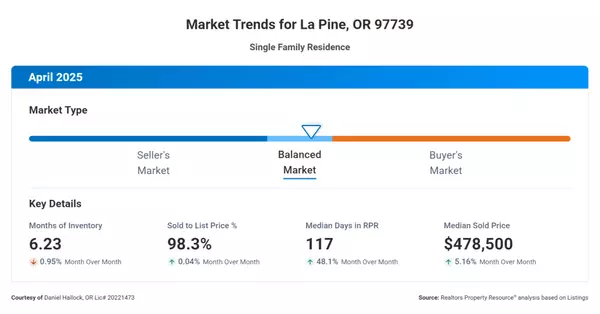

The "high" in Central Oregon's "High Desert" refers to its significant elevation above sea level. The broader Oregon High Desert region averages between 4,000 and 6,000 feet in elevation. Specific communities within Central Oregon also sit at considerable altitudes: Bend is at 3,623 feet, La Pine at roughly 4,235 feet, Sisters at about 3,180 feet, and Sunriver at approximately 4,165 feet. Even Redmond, at 3,075 feet, is notably elevated. This elevation is a key distinguishing factor from many lower-lying, hotter deserts.

While it is colloquially known as "High Desert," Central Oregon technically receives too much precipitation to be classified as a "true" desert by strict scientific definitions. True deserts typically receive less than 10 inches of annual rainfall, whereas Central Oregon generally receives between 10 to 30 inches annually, with Bend averaging around 11.36 inches. Biologically, much of the region is classified as a "shrubland" or "shrub-steppe" ecosystem. This landscape is dominated by low, widely spaced shrubs like sagebrush, bitterbrush, and western juniper, along with grasslands and lava flows, rather than the iconic cactus forests often associated with traditional, hotter deserts. The term "High Desert" has become a popular regional identity, reflecting its relative aridity and elevation compared to the rest of Oregon, rather than a narrow scientific classification. This popular usage underscores how local perception and regional identity can shape geographical nomenclature.

The substantial elevation of Central Oregon fundamentally influences its temperature profile, creating a unique "cold desert" or "cool semi-arid" environment that stands apart from hotter, lower-latitude deserts. While deserts are known for high temperatures, Central Oregon's high elevation means its climate, though arid, is not consistently hot year-round. The region experiences warm summers with average highs in the mid-80s, but also mild winters with significant snowfall, averaging 23 inches annually in Bend. This contrasts sharply with deserts like the Sonoran, which are lower in elevation and latitude, and thus generally hotter year-round. The Great Basin Desert, which encompasses parts of Oregon's High Desert, is specifically identified as a "cold desert" with "very cold winters" and "considerable snow and hard frost," where freezing temperatures are more limiting to plant life than aridity alone. This highlights that the "high" in "High Desert" is not just about altitude, but how that altitude shapes a distinct temperature regime, preventing the extreme, sustained heat typical of lower-elevation, lower-latitude deserts.

To further illustrate these distinctions, consider the following comparison:

Table 1: Central Oregon High Desert vs. Typical "True" Deserts

|

Characteristic |

Central Oregon (High Desert/Shrub-Steppe) |

Typical "True" Desert (e.g., Sonoran/Mojave) |

|

Average Elevation |

3,000 - 6,000 feet (Bend ~3,600 ft) |

Generally lower, some below sea level (Mojave 300-6000 ft, Death Valley -282 ft) |

|

Annual Precipitation |

10 - 30 inches (Bend ~11.36 inches) |

Typically < 10 inches |

|

Dominant Vegetation |

Sagebrush, bitterbrush, western juniper, grasslands |

Cacti (e.g., Saguaro), creosote bush |

|

Winter Temperature |

Mild winters, significant snowfall, cold but not extreme freezing |

Can be cold with hard freezes (Mojave, Chihuahuan, Great Basin), but Sonoran is warmer |

III. The Cascade Mountains: Central Oregon's Rain Shadow Guardian

The primary climatic force shaping Central Oregon's arid conditions is the imposing Cascade Range. These mountains, with their tallest peaks topping 10,000 feet in elevation, act as a formidable barrier to moisture-laden air originating from the Pacific Ocean. As prevailing westerly winds push this moist air eastward, it is forced to rise over the Cascades. As the air ascends, it cools, causing its water vapor to condense and fall as rain or snow on the western, windward slopes. This process is evident in the dramatically wetter western slopes of Washington State's Cascades, which receive over 4 meters of annual precipitation.

By the time this air descends on the eastern side of the mountains, over Central Oregon, it has lost most of its moisture, becoming significantly drier and warmer. This phenomenon is known as the "rain shadow effect". The Cascade rain shadow is recognized as one of the strongest in the world, creating a stark contrast in precipitation across the state. For instance, areas in the eastern Columbia River basin receive less than 25 cm (approximately 10 inches) of precipitation annually, a dramatic difference from the western ridges. This powerful rain shadow effect is the single most significant climatic determinant of Central Oregon's aridity. The "desert" aspect of Central Oregon's name is not merely due to its geographic location, but fundamentally a direct consequence of the immense meteorological power of the Cascade Mountains, which create an extreme climatic divide across the state.

This powerful rain shadow effect drastically reduces the annual rainfall in Central Oregon to a mere 12-18 inches, a stark contrast to the lush, wet conditions west of the Cascades. This aridity is the fundamental reason for the region's "desert" characteristics, shaping its entire ecosystem. The reduced precipitation means that winter snowpack in the mountains becomes a critically important water source, sustaining rivers and reservoirs through the dry summer months. This has significant implications for water resource management, providing hydroelectric power, irrigation water, and drinking water, and is crucial for agriculture in the region, where irrigation has transformed areas into productive agricultural lands.

IV. A Landscape Forged by Fire and Ice: Geology of the High Desert

The very foundation of Central Oregon's High Desert terrain is a testament to immense geological forces. The overwhelming majority of the landscape was formed by a deep sequence of liquid lava flows, primarily basalt, that repeatedly erupted from miles-long vents. These vast flows spread across thousands of square miles of the interior Northwest, with most occurring between approximately 30 and 10 million years ago. Even the region's sedimentary deposits are largely derived from volcanic ash that settled in ancient lake basins. This ancient volcanic activity is the fundamental geological basis for the "rocky upland" and "high" characteristics that defined the initial usage of "High Desert." The massive lava flows laid the initial groundwork, creating the rocky, elevated plateaus characteristic of the area.

The southern portion of Oregon's High Desert is an integral part of the larger North American Basin and Range Province. This distinctive landscape is characterized by a series of alternating, generally north-south trending mountain ranges and broad, almost level basins. These features were formed during the Pliocene Epoch (10 to 2 million years ago) by extensive faulting, driven by the forces of global plate tectonics. Examples include prominent fault-block ranges like the Warner Mountains, Abert Rim, and Steens Mountain, which rise dramatically from subsided basins such as the Chewaucan and Alvord Basins, and the Warner and Catlow Valleys.

The High Desert's landscape was further sculpted by the Pleistocene Epoch, or Ice Age (from 2 million to about 12,000 years ago). During this period, the climate was slightly colder and wetter than today, leading many of the enclosed basins to become vast freshwater lakes, some nearly three hundred feet deep. At the highest elevations, glaciers formed, carving large U-shaped valleys into the layers of basalt. As the climate warmed and dried after approximately 12,000 years ago, these glaciers retreated, and the large bodies of fresh water steadily shrank. This left behind the shallow, often alkaline lakes like Abert Lake, vast dry playas such as the Alvord Desert, and sagebrush-filled expanses like the Catlow and Fort Rock Valleys that define much of the modern landscape. The complex interplay of volcanism, tectonic forces, and subsequent glacial and pluvial cycles created the diverse topography, varied soil types, and unique hydrological features that define Central Oregon's "High Desert" ecosystem. This multi-layered history results in a landscape of varied elevations, distinct soil compositions, and unique water features, which in turn support the region's specific and diverse plant and animal communities.

V. A Name with History: The Evolution of "High Desert"

The name "High Desert" for Central Oregon is a relatively modern development in the region's history. Before it became widely accepted, Euro-American explorers and settlers applied other descriptive names to southeastern Oregon's dry landscape. Maps from the 1850s into the 1890s commonly featured terms like "Sage Plains," "Sage Desert," and even "Great Sandy Desert." As travel across the area increased after 1900, some cartographers simply marked the region with the warning "Desert." It was apparently during the 1920s that long-distance travelers began to refer to the region as the "Oregon Desert".

The term "high desert" itself may have first appeared on Oregon maps in the early twentieth century. Initially, it was used to designate a specific "rocky upland area" near the center of the state, particularly in northernmost Lake County and southeastern Deschutes County. Local ranchers in this specific area played a key role in popularizing the term. They distinguished the flat expanse of the Fort Rock-Christmas Lake Valley basin as "low desert" and referred to the higher-elevation, rockier upland immediately to its north (an area now traversed by Highway 20 between Riley and Millican) as "high desert". This localized distinction highlights a practical, on-the-ground understanding of elevation and terrain.

Following World War II, the term "Oregon High Desert" gained significant popularity and was increasingly applied to a much larger geographic area, eventually encompassing virtually all of Oregon east of the Cascade Range, excluding the Blue Mountains. While its precise geographic definition remains informal and has evolved, "High Desert" is now "relatively well accepted" as the name for southeastern Oregon's high-elevation, semi-arid-to-arid steppe lands. The evolution of the term "High Desert" reflects a dynamic process of human interaction with and perception of the landscape, moving from specific local descriptors to a broader, more generalized regional identity. This progression from "Sage Plains" to "Great Sandy Desert" to "Oregon Desert" and finally "High Desert" illustrates how early perceptions focused on dominant vegetation or perceived aridity, eventually leading to a popular and generalized term as the region became more known and accessible. The name "High Desert Country" is thus a living historical artifact, reflecting how human settlement, travel, and popular discourse have shaped our collective understanding and naming of this unique landscape over time.

VI. Life Thrives: Adaptations in the High Desert Ecosystem

Central Oregon's high desert landscape, a mosaic of sagebrush steppe, vast pine forests, and volcanic terrain, supports a remarkable array of plant life. Native plants are exceptionally well-adapted to the cool, dry environment, showcasing various drought-tolerant strategies. Dominant species include Sagebrush, a key component of the landscape valued for its aromatic foliage and its role in supporting wildlife like sage-grouse. Other common examples are Bitterbrush, which provides important forage for wildlife, and Western Juniper, a characteristic drought-tolerant tree offering habitat and food. Oregon Grape, Balsamroot, various Lupines, and Milkweeds (crucial for monarch butterflies) also thrive here. Beyond common species, the region is a haven for several rare and endemic plant species, such as Pumice moonwort (

Botrychium pumicola), Ochoco lomatium (Lomatium ochocense), Peck's milkvetch (Astragalus peckii), Lemmon's milkvetch (Astragalus lemmonii), and Henderson's needlegrass (Achnatherum hendersonii).

The high desert supports a diverse array of wildlife that have developed remarkable and often surprising strategies to survive the arid, high-elevation conditions, including significant cold winters. The Pygmy Short-horned Lizard, a tiny reptile rarely more than seven centimeters long, exhibits an extraordinary adaptation to cold. It routinely hibernates by burying itself just a few centimeters below the sand surface, freezing solid for months at a time. When spring warmth returns, these lizards thaw unharmed, allowing them to survive snowbound mountain summits at nearly 2400m elevation. This reptile's ability to endure freezing temperatures is a testament to the specialized adaptations required for life in this environment.

Wilson's Phalaropes, peach and gray shorebirds, visit Lake Abert in massive numbers, sometimes up to 100,000 individuals. To prepare for their immense 5,000-mile non-stop migration to South America, they engage in "vortex feeding" to bring food to the surface and "hyperphagia," a process where they double their weight in just a few weeks by eating almost continuously. This rapid weight gain is a critical adaptation for their long, arduous journey. The Pacific Lamprey, an ancient anadromous species, predates dinosaurs by over 200 million years and still plies the rivers of Oregon's high desert. It holds profound cultural, spiritual, and subsistence value for Native American tribes in the Columbia River Basin. Another unique adaptation is seen in porcupines, which, unlike many mammals in cold, high-altitude climates, do not hibernate and remain active throughout the year, demonstrating a distinct strategy for winter survival. Other notable wildlife found in the region includes river otters, bobcats, various birds of prey (owls, eagles, hawks), Gila monsters, desert tortoises, rattlesnakes, turtles, burrowing owls, bull trout, and redband trout.

The "High Desert" is not a barren wasteland but a vibrant, ecologically resilient landscape where life has evolved highly specialized and often surprising strategies to thrive in challenging conditions. The specific adaptations of the pygmy short-horned lizard, Wilson's Phalaropes, and non-hibernating porcupines are remarkable examples of evolutionary specialization. This directly contradicts the common misconception of deserts as lifeless or desolate, highlighting the ingenuity of life in extreme environments. However, while celebrating the thriving life, it is important to note that the unique and highly adapted sagebrush steppe ecosystem of Central Oregon's High Desert is among the most threatened in North America. This vulnerability underscores the critical importance of conservation efforts. Understanding the factors that define Central Oregon as "High Desert Country" inherently leads to recognizing the fragility of its unique ecosystems, fostering a greater appreciation for and commitment to protecting its specialized biodiversity from ongoing threats.

VII. Central Oregon's Climate at a Glance: Data Insights

Central Oregon is characterized by warm, dry summers and mild, snowy winters. The region enjoys over 290 sunny days per year, with low humidity that makes even the hottest summer days feel comfortable without the need for air conditioning.

For Bend, a central community in the High Desert, the average annual climate data provides a clear picture:

-

Average annual precipitation: 11.36 inches

-

Average annual snowfall: 23 inches

-

Average high temperature: 60°F

-

Average low temperature: 33°F

Central Oregon experiences four distinct seasons, each with its own charm and weather patterns:

-

Spring (March-May): Temperatures gradually rise, with average highs from 52°F to 66°F. Rainfall is moderate, ranging from 0.7 to 1 inch per month. Early spring may see some snowfall, but it typically tapers off by May.

-

Summer (June-August): These are the warmest and driest months, with average high temperatures ranging from 74°F to 84°F. Precipitation is at its lowest, typically between 0.3 and 0.7 inches per month, and snowfall is virtually nonexistent. July is generally the hottest month.

-

Fall (September-November): Temperatures begin to cool, with average highs dropping from 76°F in September to 49°F in November. Precipitation increases towards winter, ranging from 0.3 to 1.3 inches per month, with the first significant snowfall usually arriving in November.

-

Winter (December-February): These are the coldest months, with average high temperatures ranging from 39°F to 46°F and average lows from 23°F to 25°F. Precipitation is highest during winter, between 1 and 2.2 inches per month, primarily as significant snowfall, averaging 5.3 to 6.4 inches per month. December is typically the coldest month.

The following table provides a detailed monthly breakdown for Bend, Oregon:

Table 2: Central Oregon (Bend) Average Monthly Climate Data

|

Month |

Average High Temp (°F) |

Average Low Temp (°F) |

Average Precipitation (inches) |

Average Snowfall (inches) |

|

January |

41 |

24 |

1.53 |

6 |

|

February |

44 |

24 |

1.09 |

6 |

|

March |

51 |

28 |

0.73 |

2 |

|

April |

57 |

30 |

0.78 |

0 |

|

May |

65 |

36 |

0.89 |

0 |

|

June |

72 |

42 |

0.70 |

0 |

|

July |

82 |

47 |

0.56 |

0 |

|

August |

81 |

46 |

0.48 |

0 |

|

September |

74 |

40 |

0.41 |

0 |

|

October |

62 |

33 |

0.60 |

0 |

|

November |

47 |

28 |

1.39 |

3 |

|

December |

39 |

23 |

2.20 |

6 |

VIII. Conclusion: A Landscape Defined by Elevation, Aridity, and Resilience

Central Oregon truly earns its moniker as "High Desert Country" through a powerful and intricate combination of factors. Its elevated terrain sets it apart, while the profound rain shadow effect of the towering Cascade Mountains creates its defining aridity. This unique landscape is underpinned by a deep geological history of ancient volcanic activity and sculpted by the legacy of ice ages. Furthermore, the very name itself has evolved over time, reflecting changing human perceptions of this distinctive land.

This is a land of striking contrasts – where majestic, snow-capped peaks meet expansive, arid plains; where ancient lava flows form the bedrock for vibrant shrub-steppes; and where a diverse array of resilient life forms not only survive but thrive despite challenging conditions. Central Oregon is a "high desert" not just in name, but in its unique blend of elevation, aridity, and its remarkably adapted ecosystems, making it a truly special place.

Understanding these multifaceted reasons deepens appreciation for Central Oregon's unique beauty and profound ecological significance. We invite you to experience the remarkable "High Desert Country" for yourself and witness its compelling story etched in the landscape and its living inhabitants.

This blog post was written with the assistance of an AI model. While the content is based on factual research and expert analysis, readers are encouraged to consult multiple sources for comprehensive understanding.

Categories

Recent Posts